Star formation is the process by which dense regions within molecular clouds in interstellar space—sometimes referred to as “stellar nurseries” or “star-forming regions”—collapse and form stars.[1] As a branch of astronomy, star formation includes the study of the interstellar medium (ISM) and giant molecular clouds (GMC) as precursors to the star formation process, and the study of protostars and young stellar objects as its immediate products. It is closely related to planet formation, another branch of astronomy. Star formation theory, as well as accounting for the formation of a single star, must also account for the statistics of binary stars and the initial mass function. Most stars do not form in isolation but as part of a group of stars referred as star clusters or stellar associations.[2]

History

[edit]

The first stars were believed to be formed approximately 12-13 billion years ago following the Big Bang. Over intervals of time, stars have fused helium to form a series of chemical elements.

Stellar nurseries

[edit]

Interstellar clouds

[edit]

Spiral galaxies like the Milky Way contain stars, stellar remnants, and a diffuse interstellar medium (ISM) of gas and dust. The interstellar medium consists of 104 to 106 particles per cm3, and is typically composed of roughly 70% hydrogen, 28% helium, and 1.5% heavier elements by mass. The trace amounts of heavier elements were and are produced within stars via stellar nucleosynthesis and ejected as the stars pass beyond the end of their main sequence lifetime. Higher density regions of the interstellar medium form clouds, or diffuse nebulae,[3] where star formation takes place.[4] In contrast to spiral galaxies, elliptical galaxies lose the cold component[definition needed] of its interstellar medium within roughly a billion years, which hinders the galaxy from forming diffuse nebulae except through mergers with other galaxies.[5]

In the dense nebulae where stars are produced, much of the hydrogen is in the molecular (H2) form, so these nebulae are called molecular clouds.[4] The Herschel Space Observatory has revealed that filaments, or elongated dense gas structures, are truly ubiquitous in molecular clouds and central to the star formation process. They fragment into gravitationally bound cores, most of which will evolve into stars. Continuous accretion of gas, geometrical bending[definition needed], and magnetic fields may control the detailed manner in which the filaments are fragmented. Observations of supercritical filaments have revealed quasi-periodic chains of dense cores with spacing comparable to the filament inner width, and embedded protostars with outflows.[jargon][6]

Observations indicate that the coldest clouds tend to form low-mass stars, which are first observed via the infrared light they emit inside the clouds, and then as visible light when the clouds dissipate. Giant molecular clouds, which are generally warmer, produce stars of all masses.[7] These giant molecular clouds have typical densities of 100 particles per cm3, diameters of 100 light-years (9.5×1014 km), masses of up to 6 million solar masses (M☉), or six million times the mass of Earth’s sun.[8] The average interior temperature is 10 K (−441.7 °F).

About half the total mass of the Milky Way‘s galactic ISM is found in molecular clouds[9] and the galaxy includes an estimated 6,000 molecular clouds, each with more than 100,000 M☉.[10] The nebula nearest to the Sun where massive stars are being formed is the Orion Nebula, 1,300 light-years (1.2×1016 km) away.[11] However, lower mass star formation is occurring about 400–450 light-years distant in the ρ Ophiuchi cloud complex.[12]

A more compact site of star formation is the opaque clouds of dense gas and dust known as Bok globules, so named after the astronomer Bart Bok. These can form in association with collapsing molecular clouds or possibly independently.[13] The Bok globules are typically up to a light-year across and contain a few solar masses.[14] They can be observed as dark clouds silhouetted against bright emission nebulae or background stars. Over half the known Bok globules have been found to contain newly forming stars.[15]

Cloud collapse

[edit]

An interstellar cloud of gas will remain in hydrostatic equilibrium as long as the kinetic energy of the gas pressure is in balance with the potential energy of the internal gravitational force. Mathematically this is expressed using the virial theorem, which states that, to maintain equilibrium, the gravitational potential energy must equal twice the internal thermal energy.[17] If a cloud is massive enough that the gas pressure is insufficient to support it, the cloud will undergo gravitational collapse. The mass above which a cloud will undergo such collapse is called the Jeans mass. The Jeans mass depends on the temperature and density of the cloud, but is typically thousands to tens of thousands of solar masses.[4] During cloud collapse dozens to tens of thousands of stars form more or less simultaneously which is observable in so-called embedded clusters. The end product of a core collapse is an open cluster of stars.[18]

In triggered star formation, one of several events might occur to compress a molecular cloud and initiate its gravitational collapse. Molecular clouds may collide with each other, or a nearby supernova explosion can be a trigger, sending shocked matter into the cloud at very high speeds.[4] (The resulting new stars may themselves soon produce supernovae, producing self-propagating star formation.) Alternatively, galactic collisions can trigger massive starbursts of star formation as the gas clouds in each galaxy are compressed and agitated by tidal forces.[20] The latter mechanism may be responsible for the formation of globular clusters.[21]

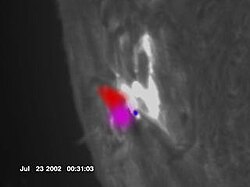

A supermassive black hole at the core of a galaxy may serve to regulate the rate of star formation in a galactic nucleus. A black hole that is accreting infalling matter can become active, emitting a strong wind through a collimated relativistic jet. This can limit further star formation. Massive black holes ejecting radio-frequency-emitting particles at near-light speed can also block the formation of new stars in aging galaxies.[22] However, the radio emissions around the jets may also trigger star formation. Likewise, a weaker jet may trigger star formation when it collides with a cloud.[23]

As it collapses, a molecular cloud breaks into smaller and smaller pieces in a hierarchical manner, until the fragments reach stellar mass. In each of these fragments, the collapsing gas radiates away the energy gained by the release of gravitational potential energy. As the density increases, the fragments become opaque and are thus less efficient at radiating away their energy. This raises the temperature of the cloud and inhibits further fragmentation. The fragments now condense into rotating spheres of gas that serve as stellar embryos.[25]

Complicating this picture of a collapsing cloud are the effects of turbulence, macroscopic flows, rotation, magnetic fields and the cloud geometry. Both rotation and magnetic fields can hinder the collapse of a cloud.[26][27] Turbulence is instrumental in causing fragmentation of the cloud, and on the smallest scales it promotes collapse.[28]

Protostar

[edit]

Main article: Protostar

A protostellar cloud will continue to collapse as long as the gravitational binding energy can be eliminated. This excess energy is primarily lost through radiation. However, the collapsing cloud will eventually become opaque to its own radiation, and the energy must be removed through some other means. The dust within the cloud becomes heated to temperatures of 60–100 K, and these particles radiate at wavelengths in the far infrared where the cloud is transparent. Thus the dust mediates the further collapse of the cloud.[29]

During the collapse, the density of the cloud increases towards the center and thus the middle region becomes optically opaque first. This occurs when the density is about 10−13 g / cm3. A core region, called the first hydrostatic core, forms where the collapse is essentially halted. It continues to increase in temperature as determined by the virial theorem. The gas falling toward this opaque region collides with it and creates shock waves that further heat the core.[30]

When the core temperature reaches about 2000 K, the thermal energy dissociates the H2 molecules.[30] This is followed by the ionization of the hydrogen and helium atoms. These processes absorb the energy of the contraction, allowing it to continue on timescales comparable to the period of collapse at free fall velocities.[31] After the density of infalling material has reached about 10−8 g / cm3, that material is sufficiently transparent to allow energy radiated by the protostar to escape. The combination of convection within the protostar and radiation from its exterior allow the star to contract further.[30] This continues until the gas is hot enough for the internal pressure to support the protostar against further gravitational collapse—a state called hydrostatic equilibrium. When this accretion phase is nearly complete, the resulting object is known as a protostar.[4]

Accretion of material onto the protostar continues partially from the newly formed circumstellar disc. When the density and temperature are high enough, deuterium fusion begins, and the outward pressure of the resultant radiation slows (but does not stop) the collapse. Material comprising the cloud continues to “rain” onto the protostar. In this stage bipolar jets are produced called Herbig–Haro objects. This is probably the means by which excess angular momentum of the infalling material is expelled, allowing the star to continue to form.

When the surrounding gas and dust envelope disperses and accretion process stops, the star is considered a pre-main-sequence star (PMS star). The energy source of these objects is (gravitational contraction)Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism, as opposed to hydrogen burning in main sequence stars. The PMS star follows a Hayashi track on the Hertzsprung–Russell (H–R) diagram.[33] The contraction will proceed until the Hayashi limit is reached, and thereafter contraction will continue on a Kelvin–Helmholtz timescale with the temperature remaining stable. Stars with less than 0.5 M☉ thereafter join the main sequence. For more massive PMS stars, at the end of the Hayashi track they will slowly collapse in near hydrostatic equilibrium, following the Henyey track.[34]

Finally, hydrogen begins to fuse in the core of the star, and the rest of the enveloping material is cleared away. This ends the protostellar phase and begins the star’s main sequence phase on the H–R diagram.

The stages of the process are well defined in stars with masses around 1 M☉ or less. In high mass stars, the length of the star formation process is comparable to the other timescales of their evolution, much shorter, and the process is not so well defined. The later evolution of stars is studied in stellar evolution.

Observations

[edit]

Key elements of star formation are only available by observing in wavelengths other than the optical. The protostellar stage of stellar existence is almost invariably hidden away deep inside dense clouds of gas and dust left over from the GMC. Often, these star-forming cocoons known as Bok globules, can be seen in silhouette against bright emission from surrounding gas.[35] Early stages of a star’s life can be seen in infrared light, which penetrates the dust more easily than visible light.[36] Observations from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) have thus been especially important for unveiling numerous galactic protostars and their parent star clusters.[37][38] Examples of such embedded star clusters are FSR 1184, FSR 1190, Camargo 14, Camargo 74, Majaess 64, and Majaess 98.[39]

The structure of the molecular cloud and the effects of the protostar can be observed in near-IR extinction maps (where the number of stars are counted per unit area and compared to a nearby zero extinction area of sky), continuum dust emission and rotational transitions of CO and other molecules; these last two are observed in the millimeter and submillimeter range. The radiation from the protostar and early star has to be observed in infrared astronomy wavelengths, as the extinction caused by the rest of the cloud in which the star is forming is usually too big to allow us to observe it in the visual part of the spectrum. This presents considerable difficulties as the Earth’s atmosphere is almost entirely opaque from 20μm to 850μm, with narrow windows at 200μm and 450μm. Even outside this range, atmospheric subtraction techniques must be used.

X-ray observations have proven useful for studying young stars, since X-ray emission from these objects is about 100–100,000 times stronger than X-ray emission from main-sequence stars.[41] The earliest detections of X-rays from T Tauri stars were made by the Einstein X-ray Observatory.[42][43] For low-mass stars X-rays are generated by the heating of the stellar corona through magnetic reconnection, while for high-mass O and early B-type stars X-rays are generated through supersonic shocks in the stellar winds. Photons in the soft X-ray energy range covered by the Chandra X-ray Observatory and XMM-Newton may penetrate the interstellar medium with only moderate absorption due to gas, making the X-ray a useful wavelength for seeing the stellar populations within molecular clouds. X-ray emission as evidence of stellar youth makes this band particularly useful for performing censuses of stars in star-forming regions, given that not all young stars have infrared excesses.[44] X-ray observations have provided near-complete censuses of all stellar-mass objects in the Orion Nebula Cluster and Taurus Molecular Cloud.[45][46]

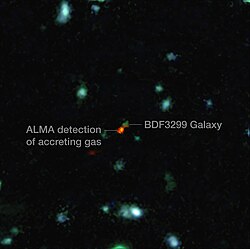

The formation of individual stars can only be directly observed in the Milky Way Galaxy, but in distant galaxies star formation has been detected through its unique spectral signature.

Initial research indicates star-forming clumps start as giant, dense areas in turbulent gas-rich matter in young galaxies, live about 500 million years, and may migrate to the center of a galaxy, creating the central bulge of a galaxy.[47]

On February 21, 2014, NASA announced a greatly upgraded database for tracking polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the universe. According to scientists, more than 20% of the carbon in the universe may be associated with PAHs, possible starting materials for the formation of life. PAHs seem to have been formed shortly after the Big Bang, are widespread throughout the universe, and are associated with new stars and exoplanets.[48]

In February 2018, astronomers reported, for the first time, a signal of the reionization epoch, an indirect detection of light from the earliest stars formed – about 180 million years after the Big Bang.[49]

An article published on October 22, 2019, reported on the detection of 3MM-1, a massive star-forming galaxy about 12.5 billion light-years away that is obscured by clouds of dust.[50] At a mass of about 1010.8 solar masses, it showed a star formation rate about 100 times as high as in the Milky Way.[51]

Notable pathfinder objects

[edit]

- MWC 349 was first discovered in 1978, and is estimated to be only 1,000 years old.

- VLA 1623 – The first exemplar Class 0 protostar, a type of embedded protostar that has yet to accrete the majority of its mass. Found in 1993, is possibly younger than 10,000 years.[52]

- L1014 – An extremely faint embedded object representative of a new class of sources that are only now being detected with the newest telescopes. Their status is still undetermined, they could be the youngest low-mass Class 0 protostars yet seen or even very low-mass evolved objects (like brown dwarfs or even rogue planets).[53]

- GCIRS 8* – The youngest known main sequence star in the Galactic Center region, discovered in August 2006. It is estimated to be 3.5 million years old.[54]

Low mass and high mass star formation

[edit]

Stars of different masses are thought to form by slightly different mechanisms. The theory of low-mass star formation, which is well-supported by observation, suggests that low-mass stars form by the gravitational collapse of rotating density enhancements within molecular clouds. As described above, the collapse of a rotating cloud of gas and dust leads to the formation of an accretion disk through which matter is channeled onto a central protostar. For stars with masses higher than about 8 M☉, however, the mechanism of star formation is not well understood.

Massive stars emit copious quantities of radiation which pushes against infalling material. In the past, it was thought that this radiation pressure might be substantial enough to halt accretion onto the massive protostar and prevent the formation of stars with masses more than a few tens of solar masses.[57] Recent theoretical work has shown that the production of a jet and outflow clears a cavity through which much of the radiation from a massive protostar can escape without hindering accretion through the disk and onto the protostar.[58][59] Present thinking is that massive stars may therefore be able to form by a mechanism similar to that by which low mass stars form.

There is mounting evidence that at least some massive protostars are indeed surrounded by accretion disks.[60] Disk accretion in high-mass protostars, similar to their low-mass counterparts, is expected to exhibit bursts of episodic accretion as a result of a gravitationally instability leading to clumpy and in-continuous accretion rates. Recent evidence of accretion bursts in high-mass protostars has indeed been confirmed observationally.[60][61][62] Several other theories of massive star formation remain to be tested observationally. Of these, perhaps the most prominent is the theory of competitive accretion, which suggests that massive protostars are “seeded” by low-mass protostars which compete with other protostars to draw in matter from the entire parent molecular cloud, instead of simply from a small local region.[63][64]

Another theory of massive star formation suggests that massive stars may form by the coalescence of two or more stars of lower mass.[65]

Filamentary nature of star formation

[edit]

Recent studies have emphasized the role of filamentary structures in molecular clouds as the initial conditions for star formation. Findings from the Herschel Space Observatory highlight the ubiquitous nature of these filaments in the cold interstellar medium (ISM). The spatial relationship between cores and filaments indicates that the majority of prestellar cores are located within 0.1 pc of supercritical filaments. This supports the hypothesis that filamentary structures act as pathways for the accumulation of gas and dust, leading to core formation.[66]

Both the core mass function (CMF) and filament line mass function (FLMF) observed in the California GMC follow power-law distributions at the high-mass end, consistent with the Salpeter initial mass function (IMF). Current results strongly support the existence of a connection between the FLMF and the CMF/IMF, demonstrating that this connection holds at the level of an individual cloud, specifically the California GMC.[66] The FLMF presented is a distribution of local line masses for a complete, homogeneous sample of filaments within the same cloud. It is the local line mass of a filament that defines its ability to fragment at a particular location along its spine, not the average line mass of the filament. This connection is more direct and provides tighter constraints on the origin of the CMF/IMF.[66]